BORDERLANDS: Conversation. Connection. Change.

This article summarizes the findings coming out of the co-creative workshop and subsequent forum held on the 28th September 2025 and 3rd October 2025 respectively. These events are organized by Vox Camerata Limited, and are part of the Community Engagement and Outreach segment of the BORDERLANDS Programme in conjunction with True Colors Project and Under The Bridge.

To start on a personal note, Audrey and I have been office mates at Aliwal Arts Centre over the last 5 years, and we've often taken the time to share bread and rely on each other for support and suggestions. I've long followed the work that she and True Colors Projects have been doing over the years, and I had the pleasure of watching the COLONY performance during the Singapore International Festival of the Arts in 2025. When she shared about the BORDERLANDS project and asked if Vox Camerata wanted to collaborate for BORDERLANDS, I jumped on the opportunity.

The premise of the BORDERLANDS programme starts by a single question:

How can we create ways to work and collaborate meaningfully with persons with disabilities ?

There are two segments to the BORDERLANDs programme. The first is the performance showcase and talk-back session which has held on Thursday, 18th September 2025 at the Esplanade Concourse. The second is the wider community engagement session, where the primary outcome was to create a toolkit that will help communities expand their capability to collaborate with persons living with disabilities. The focus of this page is on the latter, where we will share insights on how the toolkit journey came along, and how we hope it becomes a call-to-action for communities to use and to make suggestions to make it more viable and meaningful.

Our Journey: The Methodology of toolkit creation

The preparatory phase of our workshop was guided by a clear and focused goal: to create a practical, user-centered toolkit that community organizers and creative enablers can use to foster truly inclusive, non-ableist collaborations involving people with disabilities. To achieve this, we committed to a multifaceted research and observation process that laid the foundation for the toolkit’s development. This meant diving deep into existing literature to understand the theories and best practices surrounding inclusive collaboration and universal design. Equally vital was immersing ourselves in the lived experience of the BORDERLANDS ensemble rehearsals, closely observing how participants with diverse abilities communicate, collaborate, and navigate challenges together. Complementing these observations, we conducted in-depth interviews with artists, directors, and facilitators to capture nuanced insights into the collaborative dynamic and power relations on the ground. By analyzing these rich data sources—fieldnotes, literature summaries, and interview transcripts—in tandem, we synthesized a comprehensive and responsive toolkit prototype designed not only as a guide but as a living document that reflects the realities and aspirations of the communities it serves.

We started by reading and analysing scholarly literature, case studies, and sector toolkits from Singapore and abroad that mapped the terrain of inclusive arts practices and universal design. Each article, best-practice guide, and academic study provided not only theoretical underpinnings but also practical insights into what works—and, just as crucially, what so often fails—when it comes to building authentic collaboration between people with and without disabilities. For instance, learning how universal design can be misapplied as a one-size-fits-all fix, instead of an iterative, context-aware approach, reminded us to build flexibility and feedback loops into every branch of the toolkit.

Concurrently, the ethnographic observations were situated at rehearsal studio of the BORDERLANDS project. Attending multiple rehearsals, we watched as performers who are with and without disabilities negotiated space, language, emotion, and intention. There were moments of seamless connection: a dancer in a wheelchair building energy into the choreography, while non-disabled peers adapted in response, showing that artistic roles can shift organically when access is prioritized in the creative process. Other times, subtle barriers surfaced—a missed cue due to inaccessible instructions or an idea not reaching the group because of communication style mismatches. Each moment, supportive or strained, was documented in fieldnotes.

As a means to triangulate our understanding of the practice, a series of in-depth interviews were conducted with individuals involved in the group: performers (both disabled and non-disabled), the artistic director, and creative facilitators. These conversations were as varied as the ensemble—some brimming with hope and agency, others reflecting on exclusion or frustration. Notable highlights of the interviews would include how even seemingly minor oversights (like the absence of rest breaks tailored for energy fluctuations) could negate the spirit of inclusion. Each transcript was combed for patterns, frustrations, and small triumphs, reinforcing the necessity for the toolkit to address both systemic issues and day-to-day realities.

The last—and perhaps most critical—step before finalizing the prototype was the process of synthesis. Fieldnotes, literature summaries, and interview transcripts were meticulously analyzed side by side. This was a dynamic dialogue across sources, asking how barriers witnessed in rehearsals matched those flagged in research, and how firsthand testimony supported—or challenged—expert prescriptions for inclusion. Where literature extolled the value of feedback loops, fieldnotes highlighted how these often failed without deliberate design. Where an interviewee spoke of agency in decision-making, we checked how this was echoed by observed group dynamics and referenced universal design frameworks.

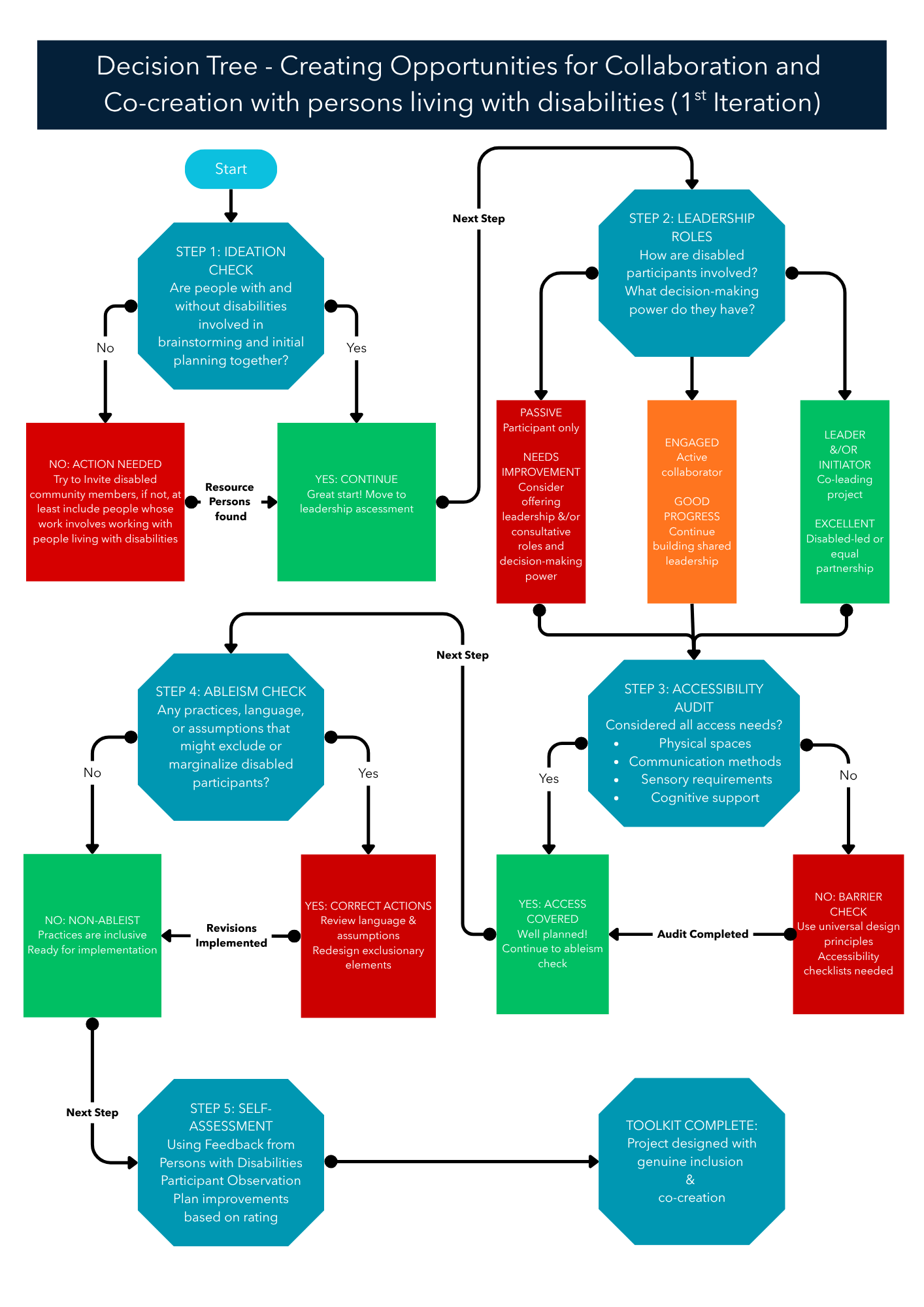

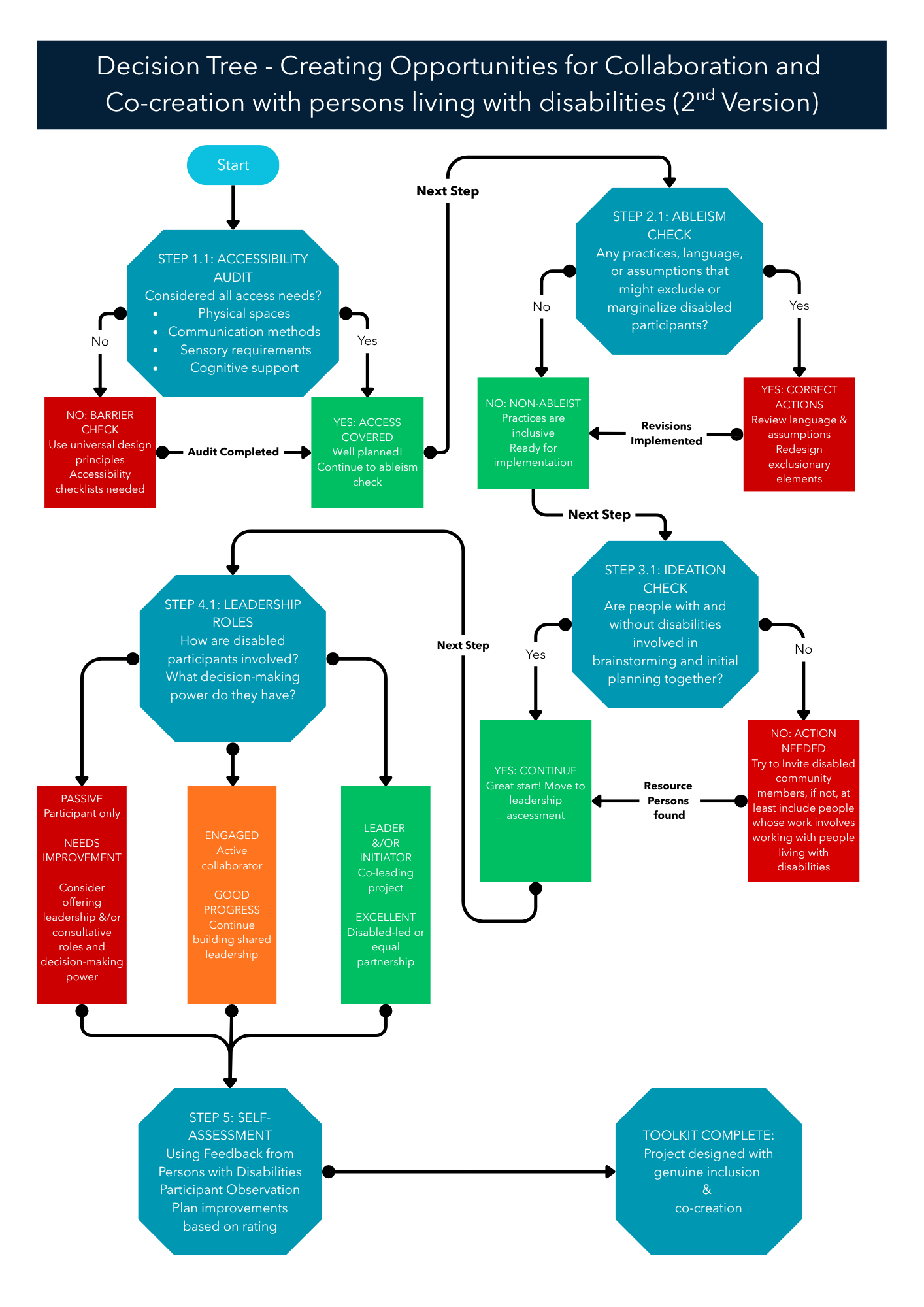

This ongoing interplay between theory and lived experience, between academic rigor and artistic messines, led to to the synthesis of the toolkit in the form of a decision tree. A decision tree is a diagram or model used to help make choices by visually mapping out a series of decisions and their possible outcomes in a tree-like structure. Each internal node of the tree represents a specific decision point or test based on available data or criteria, while each branch reflects the results or options from that point, and each leaf node at the ends of the branches signifies a final decision or outcome.

More importantly, decision trees are responsive, scenario-tested guides, constructed to prompt reflection, equip with resources, and spark change in real community projects. The final prototype, unveiled at the workshop, was thus the product of research, observation, dialogue, and iterative analysis—a living toolkit crafted to support vibrant and equitable collaboration from the ground up.

The Workshop Experience

The workshop itself was intentionally designed with two main goals at its heart: to test the newly developed inclusive collaboration toolkit in real-world scenarios, and to spark honest, generative conversations about what true inclusion looks like in practice. To achieve these aims, the method was intentionally participatory and reflective. Each segment encouraged every participant—regardless of prior experience or background—to move beyond surface-level feedback and delve into the deeper dynamics of decision-making, access, and agency. We structured the workshop around stress-testing the toolkit on case studies, open dialogue, and guided group reflection, drawing directly from field observations and interview insights. By alternating between structured activities and organic discussion, the workshop offered space for both critical analysis and creative problem-solving. This approach not only tested the toolkit’s clarity and usefulness but also surfaced new questions and ideas, ensuring that the tool becomes a living resource shaped by the community’s real needs and wisdom.

To that end, we gathered four community activators, each bringing a different background and passion for socially engaged art. The session began with a warm welcome and a discussion on what ableism looks like in our everyday work. During the workshop, one of the most profound moments emerged from a candid conversation about what ableism means within the unique context of Singapore. While the city-state is often praised for its efficiency and modern infrastructure, participants recognized that these very traits can sometimes mask deeper inequalities faced by persons with disabilities. Ableism here is not always overt segregation or exclusion. Instead, it frequently hides behind rigid systems, unexamined assumptions, and a narrow definition of “normal.” One participant reflected on how public policies and urban planning, despite good intentions, often prioritize able-bodied norms, unintentionally sidelining disabled people. For example, while wheelchair ramps and elevators are common, less visible barriers—like inaccessible communication methods or inflexible social expectations—persistently limit participation. The conversation also moved towards how environmental features determine whether persons with disabilites are included or exluded, which lead us to talk about Universal Design Principles. We have included Annex A - Summary: Universal Design Principles below to that summarizes the concept of Universal Design Practices for ease of reference.

Another insight was about societal attitudes. In Singapore’s fast-paced, success-driven culture, there can be a tacit bias that equates ability with worth and productivity. This dynamic creates pressures on disabled people to conform or prove their value in ways that non-disabled peers may not experience. One of the participants shared how such expectations sometimes create invisible ceilings in creative and leadership opportunities, even within inclusive environments. The group agreed that addressing ableism in Singapore requires more than physical access alone. It demands broad cultural shifts—valuing diverse ways of being and participating, challenging stereotypes, and fostering genuine empathy. Importantly, it means empowering disabled individuals not only as beneficiaries but as leaders and co-creators shaping the society they live in.

This conversation enriched the workshop by grounding the toolkit in lived realities and cultural nuances, reinforcing that strategies to dismantle ableism must resonate with local contexts to be truly effective and transformative. This set a thoughtful tone, where everyone felt comfortable sharing experiences and raising questions. The group then dove into the heart of the session—a decision-tree toolkit designed to guide planners through the complexity of inclusive project design. The decision tree is a planning guide that also informs us at the meta-cognitive level on how inclusion is throught through and operationalised. Step by step, it prompts users to consider who is at the table during ideation, assess leadership roles, audit accessibility needs, flag ableist assumptions, and build continuous feedback loops. Practically applying this framework to two contrasting scenarios—a community garden project in a neighborhood with older residents, and a heritage trail in Kampung Glam—sparked lively discussion. Participants identified challenges and brainstormed creative solutions with an eye to breaking down exclusionary practices.

As the workshop progressed to hands-on testing of the toolkit, it quickly became evident that each participant brought their own starting point regarding universal design principles and inclusive practice. Some were familiar with accessibility guidelines and had experience integrating disability access from the earliest planning stages. Others were encountering these concepts in depth for the first time, bringing fresh but unpracticed perspectives. This diversity sparked a lively and constructive discussion about the structure of the decision tree itself. While the prototype initially reflected a familiar project-planning sequence—beginning with ideation and partnership development—participants observed that, in practice, many organizations and individuals would benefit from flagging disability access considerations much earlier, regardless of their starting point or awareness.

The group proposed reconfiguring the decision tree so that disability access checks are not a mid-stream or afterthought step, but instead positioned at the top, serving as a gateway to every other decision in the process. One participant remarked, “If we know from the start that access is non-negotiable, it changes the way we think about every subsequent choice.” This reordering not only helped “level the playing field” for people newer to universal design but also ensured that experienced advocates could confidently build accessibility into the DNA of their projects.

By the end of this session, the group agreed that making disability access checks an upfront requirement sends a strong message: true inclusion isn’t an add-on or a box to tick at a later stage—it’s foundational. This insight will guide the next iteration of the toolkit, reinforcing a culture where equitable participation is built from the ground up, no matter the user’s background or starting familiarity with inclusive design. The workshop came to life when participants rated their projects’ inclusiveness on a simple continuum: from “Let’s Try More” to “Awesome Outcomes.” This reflective moment reminded everyone that change is ongoing and that the journey toward inclusive collaboration is iterative, requiring commitment, humility, and persistence.

The Public Forum: Launching the Toolkit and Advancing Inclusion Beyond Tokenism

Following the workshop, we held a public forum to officially launch the inclusive collaboration toolkit. This forum marked an important moment to contextualize and deepen the conversation about inclusion in the wider communities. Our forum allowed the participants to explore the discourse beyond simplistic frameworks, inviting participants to engage with why genuine, equitable collaboration matters, and how it transforms both art and community.

The event provided an open space for interested members of the public to learn about the work we have accomplished, and to hear directly from those who have been intimately involved in its creation—artists, facilitators, and community organizers alike. This transparency was intentional. We wanted attendees to see not just a finished product, but an evolving ecosystem shaped by diverse lived experience and ongoing dialogue.

We were honored to feature Ms Kavitha Krishnan, Artistic Director of Maya Dance Theatre and DADC, as our keynote speaker. Her powerful reflections on disability arts leadership set a thoughtful tone, weaving artistic vision with social justice. Ms Audrey Perera, the producer of BORDERLANDS, expertly moderated this keynote dialogue, creating an inclusive and insightful exchange that resonated deeply with the audience.

The forum’s breakout sessions were facilitated by two workshop participants, Dr. Victor Gan and Mr. Faris Ridzuan, whose firsthand experience with the toolkit enriched the discussions. The conversations were dynamic and reflective, as participants grappled with questions of access, leadership, and collective agency. Attendees actively contributed suggestions and feedback on the decision tree toolkit itself, using post-it notes to annotate areas for improvement and expansion. This participatory approach reinforced the forum’s spirit: building together, listening actively, and valuing multiple perspectives.

Overall, the forum encapsulated a vibrant community moment—educating, listening, and connecting. It reaffirmed our collective commitment to move past tokenism toward flourishing, disability-led collaboration that animates art and community life. The energy and ideas generated promise to fuel ongoing refinement of the toolkit and inspire similar initiatives beyond our immediate circle.

Moving ahead: A toolkit that grows with feedback and experiences

This workshop and forum are just the beginning. The decision tree toolkit we stress-tested will evolve with community insights, becoming a practical, user-friendly companion for organizers seeking to transform their work. More importantly, it serves as a reminder that inclusion is an active process requiring reflection, dialogue, and courage.

I invite you, whether an artist, organizer, policymaker, or community member, to join this ongoing journey toward arts and community spaces that celebrate every voice and talent. Together, we can co-create vibrant, equitable, and joyful cultures where everyone belongs.

BORDERLANDS was produced by True Colour Project. The performance was a artistic collaboration with Under the Bridge Collective, and community engagement initiative is a collaboration with Vox Camerata Limited.

This project was made possible by the support of the National Youth Council, The Ministry of Culture, Community, and the Youth, and the Royal Cambodian Embassy of Singapore.

Annex A

Summary: Universal Design Principles

Universal design principles provide a foundational approach for developing projects that welcome persons with disabilities as full collaborators—not only participants. These principles, developed and internationally referenced in both community and design sectors, support meaningful engagement, co-creation, and equal agency across diverse abilities.[1][2][3]

Seven Universal Design Principles for Collaborative Projects

|

Principle |

How It Applies to Projects Involving Disabled Collaborators |

Examples in Practice |

|

Equitable Use |

Design is useful and accessible to people with diverse

abilities. Avoids segregation and stigmatization. |

Roles are open to all; project info is in multiple formats[1][3]. |

|

Flexibility in Use |

Accommodates a wide range of preferences and abilities.

Provides multiple methods of engagement. |

Meetings allow written, spoken, or visual input; adaptable

schedules[1][3]. |

|

Simple and Intuitive Use |

Easy to understand, regardless of user’s experience, language,

or cognitive skills. |

Instructions are clear, jargon-free; processes are

straightforward[3]. |

|

Perceptible Information |

Ensures key information is communicated effectively, even with

sensory differences. |

Materials include captions, audio, high contrast visuals,

images[3]. |

|

Tolerance for Error |

Minimizes hazards and negative outcomes of accidental actions. |

Feedback forms allow corrections; misunderstood instructions

are easily clarified[3]. |

|

Low Physical Effort |

Can be used efficiently and comfortably with minimal fatigue. |

Tasks can be performed seated/standing; heavy lifting is

eliminated[3]. |

|

Size and Space for Approach/Use |

Provides appropriate space for approach, reach, and

manipulation for all users. |

Meeting rooms accommodate wheelchairs; tools are accessible to

all[1][2]. |

Real-World Applications in Collaborative Projects

· Barrier-Free Movement: Spaces designed for easy access, including ramps, lifts, and wide passageways, support independent movement for both disabled and non-disabled team members.[2]

· Communication Choices: Offer multiple channels—sign language, braille, audio, visual cues, easy-to-read text—for all participants to share ideas and feedback.[3]

· Adaptive Tasks & Roles: Meetings and project activities remain flexible to suit different working speeds, sensory preferences, and communication needs.[1]

· Feedback & Error Tolerance: Encourage honest feedback and make it easy for collaborators to correct mistakes or misunderstandings without stigma.[3]

· Inclusive Technology: Use digital platforms with accessibility features (e.g., captions, screen readers, high-contrast interfaces) to involve remote or less mobile collaborators.[3]

Universal design principles shift the project lens away from “accommodating” disabilities as an add-on. Instead, they emphasize planning for diverse participation, leadership, and creativity from the very start—helping build truly collaborative processes that benefit and value everyone involved.[2][1][3]

References:

1. https://universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design/the-7-principles

2. https://enablingvillage.sg/universal-design/

3. https://footholdtechnology.com/news/universal-design-examples/

4. https://www.asla.org/universaldesign.aspx

5. https://cvision.org/learn-advocate/universal-design/

7. https://www.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/336323/best-practice-design-principles.pdf

9. https://doit.uw.edu/brief/universal-design-process-principles-and-applications